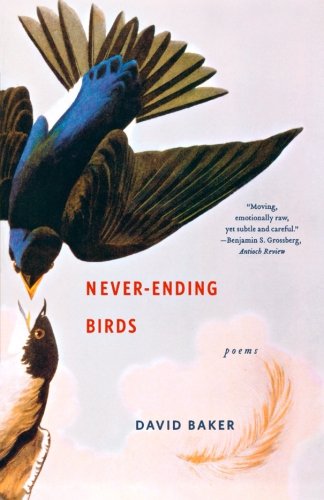

![]() American transcendentalism may be English romanticism by another name. Whatever the case, David Baker is the brilliant product of this essential Anglo-American past. He is now a major national figure, a man of letters singular in his sense of history and his protean talent. Never-Ending Birds, his new poetry collection, advances as well as reaffirms the fundamentals of his power: in his hands, common nature – which is also his human subject – is not only palpable but mindful, and at, intensely, the same time. His natural world is a thinking world, in which critical experience becomes an act of meaning, a work of art, and through the discovered word a finding.

American transcendentalism may be English romanticism by another name. Whatever the case, David Baker is the brilliant product of this essential Anglo-American past. He is now a major national figure, a man of letters singular in his sense of history and his protean talent. Never-Ending Birds, his new poetry collection, advances as well as reaffirms the fundamentals of his power: in his hands, common nature – which is also his human subject – is not only palpable but mindful, and at, intensely, the same time. His natural world is a thinking world, in which critical experience becomes an act of meaning, a work of art, and through the discovered word a finding.

– STANLEY PLUMLY

![]() David Baker manages to connect personal history to a broader canvas — American history, literary history, history of sport, natural history — the understanding of the personal as historical is what animates [this] unforgettable voice. As personal as the poems get, they are meant to be understood within a dramatic collective vision.

David Baker manages to connect personal history to a broader canvas — American history, literary history, history of sport, natural history — the understanding of the personal as historical is what animates [this] unforgettable voice. As personal as the poems get, they are meant to be understood within a dramatic collective vision.

David Baker is a profound poet who inhabits the natural world and the realm of the arcane with equal ease. He draws on many sources — from Maurice Blanchot to Cabeza de Vaca to the jeremiads of the puritan Michael Wigglesworth — to re-examine the map of emotional history. All histories, even the personal, are taken up, finally, into natural history. If the biding place of intimacy and love is broken — there is the consolation of the larger shapes that we make as an “us” — in poetry, in science, in translation and typology — and David Baker is eloquently at home in the protean shapes.

-CAROL MUSKE-DUKES, HUFFINGTON POST

![]() Well observed, careful and shot through with sadness, this eighth set of poems from Ohio resident Baker (Midwest Eclogue) is his best: syllabic stanzas, occasional rhyme, and short, clear looks at nature frame a life that almost came apart in middle age: we read of the poet’s days with his young daughter, and of what appears to be his recent divorce. “When a lark flies/ up, I know its name,” writes Baker–it is no boast: he returns over and over to the natural history of the Midwest, its meadows and exurbs, where “Hummer” means both a tiny bird and a gargantuan vehicle. Baker’s daughter’s childhood, his own teen years, middle age and approaching death get attention from his exacting eye. And as he looks hard at animals, they look back at him: he sees, in a poem about Virgil, how “the oval eyes/ of goats and sheep/ turn rounder as the day/ goes down.” Like Marianne Moore and Amy Clampitt, this poet likes to borrow from earlier texts: swaths of quotations from 17th-century prose can overwhelm his quiet verse. Yet most of the time Baker’s terms remain his own: “To see each thing clear/ is still not to see// a thing apart from/ words or our wild need.” (Oct.)

Well observed, careful and shot through with sadness, this eighth set of poems from Ohio resident Baker (Midwest Eclogue) is his best: syllabic stanzas, occasional rhyme, and short, clear looks at nature frame a life that almost came apart in middle age: we read of the poet’s days with his young daughter, and of what appears to be his recent divorce. “When a lark flies/ up, I know its name,” writes Baker–it is no boast: he returns over and over to the natural history of the Midwest, its meadows and exurbs, where “Hummer” means both a tiny bird and a gargantuan vehicle. Baker’s daughter’s childhood, his own teen years, middle age and approaching death get attention from his exacting eye. And as he looks hard at animals, they look back at him: he sees, in a poem about Virgil, how “the oval eyes/ of goats and sheep/ turn rounder as the day/ goes down.” Like Marianne Moore and Amy Clampitt, this poet likes to borrow from earlier texts: swaths of quotations from 17th-century prose can overwhelm his quiet verse. Yet most of the time Baker’s terms remain his own: “To see each thing clear/ is still not to see// a thing apart from/ words or our wild need.” (Oct.)

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

![]() In his ninth collection of poems, David Baker has seemingly solidified his stand in the American poetry scene. In this four-fold offering (part map, part chronicle, part autobiography and part travelogue) the reader gets the wordplay and titular language one expects from Baker, but they also get a glimpse of his expectations for his own sense of being. In fact, the power of these poems is enough to keep the reader on edge while the viscosity of each section makes for a lucidity often unrivaled among Baker’s contemporaries. His idea of nature and nurture combine to form an “acid analgesic/ for healing (headache, heartache, shredded/ muscle, sore or torn tendon)” and life’s many other ills.

In his ninth collection of poems, David Baker has seemingly solidified his stand in the American poetry scene. In this four-fold offering (part map, part chronicle, part autobiography and part travelogue) the reader gets the wordplay and titular language one expects from Baker, but they also get a glimpse of his expectations for his own sense of being. In fact, the power of these poems is enough to keep the reader on edge while the viscosity of each section makes for a lucidity often unrivaled among Baker’s contemporaries. His idea of nature and nurture combine to form an “acid analgesic/ for healing (headache, heartache, shredded/ muscle, sore or torn tendon)” and life’s many other ills.

-THE STRAND